FrontendOps

I had recently the privilege to speak about FrontendOps at the last Thoughtworks XConf EU in UK, Germany and Spain. You can find my presentation slides here and at some point soon a video of the talk will be made available. For now if you are interested to the topic what follows is essentially my talk transcript.

Update 14.11.18: a video of my talk is now available here.

This article describes the journey towards my definition of FrontendOps and why I think it’s an important concept in the context of building web user interfaces.

Some of you may think FrontendOps is just another buzzword I came up with. I am actually not the one who coined this term in the first place. Around 5 years ago Alex Senton was already speaking about FrontendOps in a Smashing Magazine article titled “The Front-end operations engineer”. He believed that already at that point we reached a stage in the frontend operations space where there was a need for a new role in teams to be created.

In the article he mentioned things like: frontend operations engineers would own external performance, they will have to master task runners, be pros at versioning, caching, etc…

Although I don’t agree that a new role in our teams is necessary to take care of these frontend operations I have to say that back then Alex observed a lot of interesting problems that are still very valid in today’s frontend landscape.

A journey towards FrontendOps

As I already mentioned I want to bring you on the same journey I embarked to get to definition of FrontendOps. So hopefully by the end of this article you will have an understanding of what is FrontendOps and why you and your team should care about it.

In the first part of the post I will describe what modern frontend work looks like today and how it evolved especially in the latest years. By the end of this part we will understand the main challenges of building web user interfaces today.

Then I will move on to the second part of the journey; here I try to find solutions to these challenges by zooming out a little from the frontend scene and observing if we can apply some lessons learned from other areas of our industry.

The last part of the talk is also the more concrete and practical one, we now have a solution to these challenges and it consists in a set of FrontendOps practices that I will describe before concluding with the definition of FrontendOps I came up with.

Let’s dive in the first part!

Modern Frontend

How did frontend development evolve in the last 20 years or so?

Let’s try to visualise this evolution on a timeline starting from 1995 till today.

Before 1995 the web was really young and JavaScript wasn’t a thing yet. We had only server side rendered static pages.

Then Netscape Communication had this vision that the web needed a way to become more dynamic. They wanted to introduce a way to create animation, interactions in the browsers. They needed a small scripting language that could interact with the DOM. This scripting language should not target software developers but mainly designers and non-programmers. Also Java was getting more and more popular in 1995 and at the time they thought that giving to this new language a Java-like syntax would have been a good idea. And that’s how JavaScript was born, a small scripting language for non-programmers that can interact with the DOM.

More or less 10 years later jQuery was released, a very imperative scripting library built on top of JS which solved a lot of cross-browsers incompatibilities. That was great because we all know how annoying can be having to write different versions of our code to support different target platforms (i.e. Internet Explorer,Safari, Firefox, etc…). jQuery also made easy to do async requests initiated by the browser; So now JS was started to be used not just to do simple animations but to also provide new content to our users without having to refresh their web pages.

And 2009 is when things get interesting for the JS community. NodeJS was born and JS, the client-side scripting language for non-programmers can now be executed also on the server side. From that time on an enormous amount of frontend tools has been created. Unit testing JS finally started to be a thing. AngularJS came out and we started to see more and more single page applications (SPAs). Now all interactions with the server happen without refreshing the page; fetching and managing data, switching routes is all managed by JS.

Today we have web components, we have libraries that provides beautiful abstraction of the DOM, I personally really enjoy working with React. It makes develop my views such a smooth experience. Today is also the time of Progressive web apps (PWAs): The evolution of SPAs. Thanks to service workers we can today offer to our users native-like experiences in our web applications. We can build push notifications and all sorts of offline capabilities. Today with IndexedDB we can even have a database in our web browsers.

It’s such an exciting time to work in the frontend space.

If I put in a graph complexity over time this is the curve I would probably draw to represent the rise of complexity to build web user interfaces.

I hope I convinced you that today in order to build fast reliable engaging experiences for our users a lot of complexity has moved from the server to the client which for the web is of course the browser.

Partitioning complexity in web applications

As I said complexity of web applications has increased a great deal not just on the front, and I would like to show you now how the industry partitioned complexity over time.

I don’t want to oversimplify but in the early 2000 a web application would have probably looked something like that. A universal monolith with a server side rendered view. Perhaps some JS would be loaded in the page to make it a little more dynamic (maybe some animations) but nothing more than that. Often this JS was not even tested because almost all of the application business logic still resided in the server.

Eventually things in the backend start to get too complex to be handled on a giant monolith and solution like the one in the middle picture started to emerge. Backend services are splitted in several independently deployable services hopefully built around different company business capabilities. Then an aggregation layer like GraphQL or an API gateway is put on top so that the frontend monolith could consume the data from these services. That’s better but we are still not doing microservices right here. All the UI specialists are still working on a big Frontend Monolith that get more and more complex over time. Teams are not fully cross functional and in order to deliver a piece of functionality 2 different teams needs to work on it. We are still organising teams based on technologies and not on products or business capabilities which is suboptimal.

So today we are seeing more and more organisations starting to adopt what here at Thoughtworks we call micro-frontends. In this case the web page is composed by including different frontends (fragments) developed by different teams. We finally have entire independently deployed and maintained verticals. Teams are autonomous but with a great degree of autonomy comes also great responsibilities.

Modern frontend pitfalls

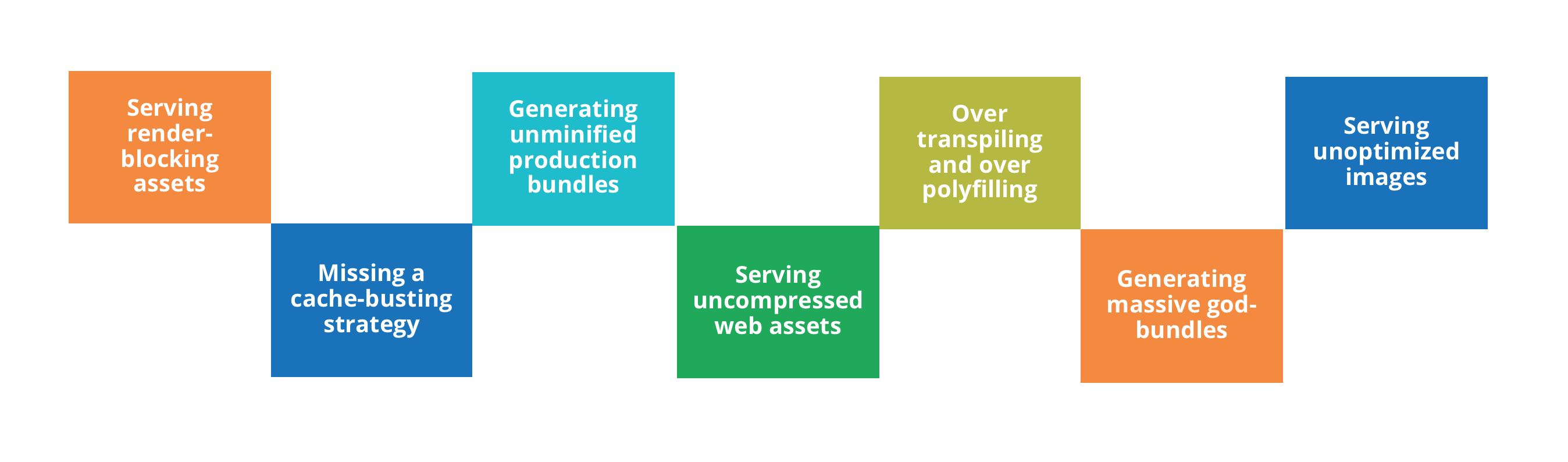

It’s not easy to partition complexity on the front without compromising user experience. I will now give you an overview of common pitfalls I often see in modern frontend projects.

Server render-blocking assets: This is the classic mistake of putting some script tag to download some JS at the top of our html page without using the defer keyword for example. The browser will stop rendering the page until the JS is downloaded parsed and executed. Time to first meaningful paint is heavily affected by this type of mistake.

Missing a cache-busting strategy: Cache invalidation is famous to be one of the hardest things to get right in software development together with naming things and off by one errors. For this one in the worst case our users will not get the new versions of our assets after a deployment because their browsers still use a cached version of them. A cache busting strategy help to delete the browser cache when our assets change. There are different way to implement this but it’s a really important one.

Generating unminified production bundles: This one explains really itself, maybe our team feels overwhelmed by all these modern JS tooling and we don’t realise that we are shipping unoptimised development bundles to our users.

Serving uncompressed web assets: Today we have really powerful compression algorithm like gzip and brotli that helps a lot to make the packets we sent over the wire way smaller and therefore provide content to our users way quicker. I have been in situation where those algorithm where not used.

Over transpiling and over polyfilling: For the one of you that are not familiar with the processes of transpiling and polyfilling. You can think of them like the steps which are necessary to make our modern JS code understandable by older browsers. I often encountered situation where JS bundles were transpiled and polyfilled to support IE8 even when the target platforms for the app were only the latest versions of chrome and firefox. This is resulting on extra code to be downloaded, parsed and executed by the users browser.

Generating massive god-bundles: God-Bundles for me are bundles that includes libraries, frameworks, application code all in one file without using any code splitting strategies. This issue sometimes leads to situation where we can even have multiple versions of the same library/framework in the same page – for example we could have a umd version of React exposed globally and a version inside the bundle itself.

Serving unoptimized images: This could be serving unnecessary big images (several KB). Perhaps don’t adopt any lazy load strategy. Don’t use the new webP format to compress images for supported browsers.

And there are more of these pitfalls, these are just a few.

Living with the consequences

I really like the concept of having to “live with the consequences”. While I was preparing the talk I re-watched the brilliant “Architecture without architects” presentations by Erik Dörnenburg, Head of Technology for TW Germany. In his talk he explains how architects don’t have to live with the consequences that their decisions have on developers.

In the same way we developers don’t live with the consequences our frontend operations have on the final user experience. When I run my application in my development machine latency is almost zero, CPU power is not a problem, Network is probably super fast. How can I understand the experience a person with an average phone under 2 or 3G network will get?

So, what capabilities are required in teams to overcome these challenges new modern frontend work bring to us?

Industry learnings

Let’s now zoom out a little from the frontend space and observe what happened in our industry in recent years.

The rise of microservices

Although I am specialised in Frontend Technologies at Thoughtworks I often get to work in cross functional teams and pair program with people that are more experienced in other areas. I get to observe what are the industry trends not only on the frontend scene but also on other fields.

What I think is a common pattern currently is how more and more growing companies are trying to move away from their monoliths in favour of a microservices architecture.

- Building cross functional teams around a product, not a project or a technology

- Adopting the Amazon philosophy “you build it, you run it”

- Automatize path to productions

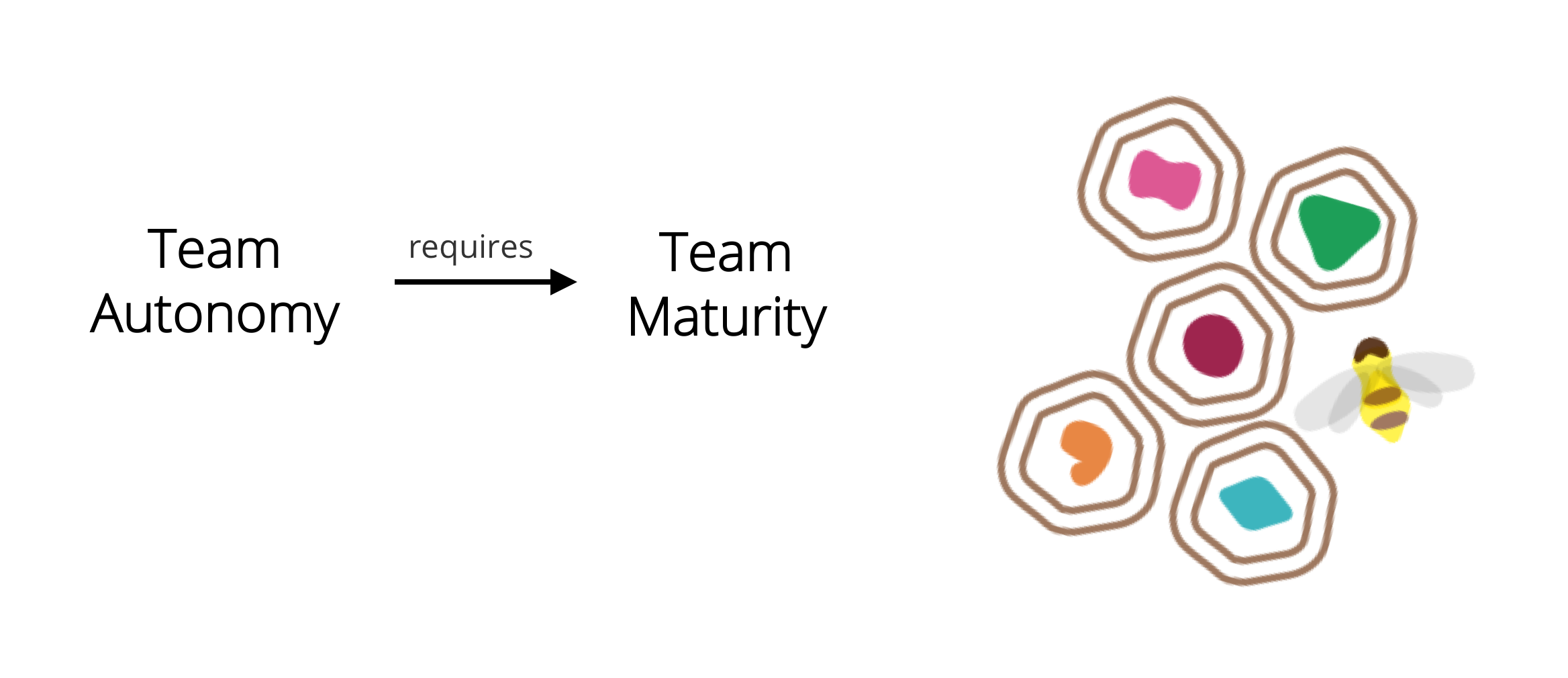

We can see how the microservice architecture paradigm is promoting a culture where team are more autonomous and the decision making process is decentralised. This approach, as you can imagine, requires an high level of maturity and a different variety of skills in teams.

When I was preparing the presentation I really enjoyed reiterating through the Microservices Prerequisites article by Martin Fowler. He said that in order to use microservices organisations need to meet some key pre-requisites.

We need to ensure to have:

- Rapid provisioning

- Basic monitoring

- Rapid application development

But most importantly we need a DevOps Culture in our teams. A sense of shared responsibility between the development and the operations part. And I cannot stress enough about this point of team feeling responsible.

A problem of culture

In the Frontend space we have a problem of culture; of developers not feeling responsible for providing great experiences to our users.

Frontend is often dismissed. The problem is that by dismissing frontend we punish our users and in the end whatever system we are building become useless if users don’t use it. I have been in many teams where Frontend is always delegated to the same person because the other team members don’t consider frontend seriously.

I am not alone to think this. Rufus Raghunath, a colleague of mine, recently wrote an excellent post in our company insights where he explained why dividing frontend from backend is an anti-pattern and often gets in the way of shipping great products at a fast pace for our users.

So what do teams really need to be successful in the era of micro-frontends? > Well my answer is a FrontendOps culture

Everyone in the team should have an understanding of how Frontend operations can impact the final user experience. This does not mean that everybody needs to be an expert in everything because is practically not possible in a cross functional team. But everybody should be open minded enough to pair with a frontend specialist and learn about how important are frontend operations to build great product for our users.

FrontendOps practices

We are now entering the final part of our journey where I would like to introduce you to a set of practices you would expect to see from team which have a mature FrontendOps understanding.

Task execution and dependencies management

6 years back Grunt landed in the JS ecosystem to help perform automatically frequent tasks such as minification, testing, etc… We generally have a Grunt plugin for each tool we want to use, so if we want to minify a file we would have a grunt-uglifyjs plugin that we could use in our task.

That said I personally find these task runners to be unnecessary abstractions because we depend on plugin authors, it’s harder to debug and documentation of plugins is disjointed from the tool itself. I think that npm or yarn scripts are powerful enough to run tasks and often are easier to live with. We already have so much tools in the Frontend space that I feel I am better off without a task runner in my projects.

So my recommendations is to stay away from task runners and use the tools you need directly with a npm or yarn scripts.

Transpilation

Today we can use the latest ecmascript features without having to worry too much if a specific target platform already implemented it. This is possible thanks to transpilation. Babel is able to parse our new ES code and generate an Abstract Syntax Tree out of it. In a second step it used plugins to transform the tree based on the user need and finally the new AST is turned into source code again.

Similar process happens for Typescript and a lot of languages that can get transpiled down to JS. There is also a CSS transpiler called PostCSS that allow us to use latest CSS features like CSS grids in older browsers

An interesting theory which is emerging these days in the JS community is about turning Frontend frameworks from runtime libraries into optimising compilers. Rich Harris, the creator of RollupJS, gave an interesting talk at the last JSConfEU about Svelte: a UI framework he built that rather than interpreting our application code at run time, convert our app into ideal JavaScript at build time.

So it really seems that compilers will become the new web Framework in a not too far future.

Bundling

We write Modern JS using the new ES Modules specification but few browsers have a good support for them. Also if our web servers are not using HTTP/2 and leveraging multiplexing yet our browser need to open a new TCP session for every resource we need to get from the server. Browsers generally settle on a limit of 6 TCP connections per host that means we cannot parallelize more than 6 requests at a time if we are still using HTTP 1.1.

This is one of the main reasons bundlers are important. Tools like webpack they bundle our assets together and they offer an high degree of configurability. They actually do more than bundling, they are able to exclude from our bundles unused code with a technique called ”tree shaking”, they can source map our code, they help us split our assets in chunks, etc…

If you have ever used webpack you probably know that configuring these tools properly is not easy task that’s why zero configuration solution like parcel are starting to get attentions these days.

Optimization

Bundling things together is not enough when we ship web assets to our users we want them to be as small as possible. Today we have a plethora of tooling to make our file smaller. The first step is to minify and mangle our JS and CSS with tools like Uglify and CSS nano. Another important thing is make sure to use a compression algorithm like gzip or brotli on the assets before shipping them to the browser.

Today we can even apply Execution optimisation to our code like constant folding, loop optimisation, etc… Prepack for example let us write normal JavaScript code, and outputs equivalent JavaScript code that runs faster on the VM (V8, SpiderMonkey). The google closure compiler is able to do similar things.

Linting and Formatting

And we know, JS is a dynamic language and because of its nature use linting tools like ESLint becomes really important to keep our codebases consistent and maintainable.

If you are on a team that does not have a lot of JS expertise I found really useful to also use a code formatter like prettier. It allows people to focus on actual problems and less in discussing about formatting conventions.

Today we also have stylelint which allows us to lint CSS. This is possible thanks to PostCSS the CSS transpiler I mentioned before.

Testing and monitoring

Testing and monitoring are probably the most important FrontendOps practices. Find a robust way to measure the experience our users will get from our application is essential to keep improving.

For example we can analyse size of production bundles on our CI pipeline to avoid introducing unnecessary libraries by mistake. We should test the speed of our application methodically using tools like Lighthouse, webpagetest, speedcurve etc… We can even set Web performance budget and for example set a resources size limit of let’s say 500 KB for our homepage.

Accessibility and vulnerabilities checks they can and should be automatized in our CI pipeline too. There is really a tool for everything today.

Developer experience

The last practice I want to cover is about Developer experience. As we saw there are so many things to take care on the frontend operations space today that it can be overwhelming for team members to have to deal constantly with all these configurations.

That’s why I really like toolboxes like create-react-app for example. They provide solid defaults for our applications and abstract away all configurations for things like linting, transpiling, testing, bundling, etc and let the team focus on shipping features. And because we are in the era of micro-frontends if your team is building several frontends for your services, it’s also a nice way to keep configurations update in all your projects. All you need to do is upgrading the toolbox-scripts dependency version to stay up to date with the latest tools.

Conclusion

So at the beginning of the article I promise you that I will be wrapping up by giving you the definition of FrontendOps I came up with. So there we go:

FrontendOps is a combination of practices and tools that makes delivering optimised web assets more efficient.

A FrontendOps culture enables teams to ship new UI features at a fast pace with the confidence of not compromising user experience.

If your team is adopting FrontendOps practices, your users will thank you.